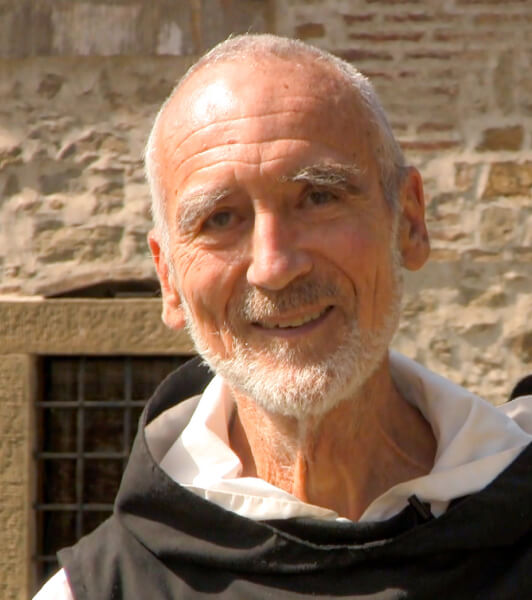

Image from an article by Michael Stillwater.

The Fountain of Thanksgiving

The Fountain of Thanksgiving

Video

Audio

Listen from 0:00 to 14:59.

This conversation is unedited. If you are pressed for time, you can skip ahead to 3:40 when the conversation officially begins. If you have the spare 3 minutes, it's worth listening to get a sense for Brother David as a regular person.

Transcript

Krista: Okay let's talk about something mundane, like what you had for breakfast. So Chris can get some levels. Yeah, and I'll lean forward. Yeah. All right. Okay, what did you have for breakfast?

David: What did I have for breakfast? I always have the same for breakfast. One of those sticky rolls, or little schnitzel.

Yeah. And peanut butter. That's it. And coffee.

Krista: What is the order of the day? What's the monastic rhythm here?

David: What do I have to do after this?

Krista: No, what's the monastic, what's the rhythm of a day? Do you have morning prayer?

David: It is pretty much like in most monasteries, but simpler than in most monasteries. We have morning prayer at 6. 30 usually. Then after that is breakfast, that's an optional thing. Then we have meditation, silent meditation together at noon, from 11. 30 to noon.

And in the evening we have Vespers, or sometimes it's combined with the Eucharist. And then that's at 5. 30 and then at 9.30, which for me seems very late, we have Compline. And that concludes the day. You are probably used to the monastic days from Collegeville and from St. John.

Krista: I actually think Compline, I'm not sure they have Compline.

David: At least they may have it just for the monks.

Krista: I think they have it just for the monks. So you were born Franz Kuno?

David: Yeah, that's correct.

Krista: In Vienna?

David: In Vienna, yeah. I'm very close to home again.

Krista: Yes, and here we are. How would you describe the religious and spiritual background of your childhood?

David: Of my childhood?

Krista: Yeah, of your childhood.

David: I think we had something at that time that was, I would call it Christendom, that doesn't exist anymore. It was a kind of combination between the Christian tradition and all the social forms and customs, it was all one, one, of one piece. And in my childhood, it was just breaking down.

It was still strong enough to give me good support. And I like support. My mother always said when I was a little baby and I wasn't very tightly wrapped as they used to wrap the babies. You'd get swaddled, yeah. I would yell. Only when I was very tightly wrapped, then I felt comfortable. So this tight wrap of Christendom where you knew exactly what to do, when, and how. That was very good for me. It was very congenial. Yeah.

And then but it, as I say, it was in, it was already breaking down. There were already wounded from World War I. I remember them either sitting by the street and begging. Or in wheelchairs, the ones who were better off in wheelchairs.

But they are a very important part of the population in my childhood as I remember. But I'm grateful for the childhood I had. I had a warm and supportive family, and then...

Krista: It was in your teenage years that the world changed so utterly.

David: That it really collapsed completely.

Krista: And also interesting to me--Austria became an occupied country, it became a fascist country, and the church's role, the church's place in that very dramatic dynamic, I mean you've described it there was something, because the church became almost a place of contrast to the culture, right?

Which it, that's one way that Christendom, that, that monolithic Christendom was coming apart.

David: Yes. Yes. I. I see it since I was exactly 12 when Hitler came, so that's, I entered my teens and I spent all my teens under Hitler and while the first decade of my life was, so to say, embedded in this unquestioned world--and then when you get into your teens, you have to rebel against that world, but instead we rebelled against Hitler, because that was then the authority.

So we were pushed into resistance. And it was very clear to us, and it was very strong. And the church was the support of it. At first in, in Austria there was such confusion that even the cardinal—it collapsed, but that was in March, and in October they were already throwing his furniture out the windows of his palace, and he was hiding in a closet, so it went pretty fast.

Yeah.

Krista: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. When you, do you think there's something about the kind of life and death stakes of religion and life that you experienced in your teenage years? Is there any connection between that and the life you chose later? It sounds like your family went to the States and you had a comfortable life, a good life.

And you chose this monastic calling, and there was, it doesn't sound to me like there was anything preordained about that or expected about that.

David: I could not really say that I chose monastic calling. It chose me. It was the other way around. We didn't expect to live, really, because when the bombs are falling left and right for a long time, and when all your friends are killed in the war, you don't think much about it, but suddenly your expectations of what you do later on are very slim or non existent.

And then suddenly the war was over and and I was happy and I was alive, to my greatest surprise. And that wasn't actually in Vienna, I was in Salzburg at the time with a girlfriend and with music and with everything that you can desire. And exactly at that time, I realized why we were so happy, because we were happy during the war and during the occupation, and we were, we had a really happy youth.

I wouldn't trade it with any other. But it occurred to me that it was because we had to be really in the present moment. Yes. We had death at all times before our eyes.

Krista: That's an incredible intensity of presence.

David: That's intensity of presence. And it, I connected it with that little sentence in the Rule of St. Benedict—to have death at all times before your eyes. And I had read that before and so it suddenly became perfectly clear to me this was the way to be joyful, because that had been the way, joyful, regardless of what happened, and if I really wanted to be that happy, that was the way. But then all the surrounding elements of monastic life and so forth, did not particularly appeal to me, and so I ran away and got one alibi after the other, studying this and studying that, and then going to the United States.

This was also a running away. I didn't have any idea that in the United States, I didn't ever think about it, but I didn't have any idea there were even Benedictine monasteries there. And then, I wasn't there very long, maybe less than half a year, and I run into this monastery and I knew this is it. I was there less than 24 hours, and I knew this was it and I'm still a member of it. Yeah. It was love at first sight.

Krista: I wonder if I want to drill down and focus this for the rest of our time, on the notion of gratitude. But I think it's really important that we've delved into the backdrop of your life and how you came to that, because there's depth and heft and gravitas.

I think gratitude is one of these words culturally that can become superficial, right? And, but we're going to talk about spiritual gratitude and the depth of that. And one, one thing you do is you use the word gratefulness sometimes rather than gratitude, and I wonder if you would talk about what is helpful about that language for you?

Of gratefulness at getting at kind of the gratitude as you have come to understand it.

David: The reason why I use the words gratitude and gratefulness and thanksgiving in the way in which I use them is that we really need different terms for our experience, and we all know from experience that moments in which this gratitude wells up in our hearts are experienced first as if something were filling up within us, filling with joy, really but not yet articulate. And then comes the point where this, the heart overflows, and we sing, and we thank somebody and to that I like a different term, and then I call that thanksgiving, and the two of them are two aspects or two phases, actually, of the process that is gratitude.

So that's why I'm using it in this way and this idea of a vessel, that becomes articulate in thanksgiving. Till it overflows, that is also very helpful in another way. It's the bowl of a fountain when it fills up and it's very quiet and still. And then when it overflows, it starts to make noise and it sparkles and it ripples.

And that is really when the joy comes to itself, so to say, when it is articulate. And for us, for many people in our culture, the heart fills up with joy, with gratefulness, and just at the moment when it wants to overflow, and really the joy comes to itself, at that moment, advertisement comes in and says no, there's a better model, and there's a newer model, and your neighbor has a bigger one.

And instead of overflowing, we make the bowl bigger and bigger. And it never overflows, it never gives us this joy, this affluent society. That means it always flows in, it doesn't overflow, it flows in and in and in and chokes us eventually. And in other countries we see very poor people who, compared to us, have practically nothing.

But they are so joyful, all the time grateful and joyful, because one little drop is enough for this bowl to overflow. It's so small. So we can learn from that. We don't have to deprive ourselves of anything, but we can learn that the real joy comes with quality, not with quantity, and that's an important distinction.

Gathering Agenda

Below is a sample summary and question that could be used for an in-person gathering. Or you can use it inspiration as you craft your own. You know your community best.

Summary

This week's conversation starter was a discussion on gratitude between podcast host Krista Tippett and Benedictine Monk David Stiendl-Rast. Gratitude is one of those exceptionally important words that can start to feel abstract or superficial if we're not careful. Thankfully, Brother David is someone who treats the word gratitude with tremendous care.

I hope you were able to listen to the entire first 15 minutes of the conversation, and I hope it gave you a sense for who Brother David is as a person. He was 12 years old when the Nazis occupied his home in Austria, and yet there is so much joy in him today. There's something in that combination that, for me, gives a weight to his thoughts on gratitude. And I feel confident that the particular kind of gratitude Brother David is talking about is not superficial.

I'm going to read for you a few quotes from the conversation to jog our memories and catch new folks up to speed.

First off, Brother David is careful to distinguish between gratitude, gratefulness, and thanksgiving.

"The reason why I use the words gratitude and gratefulness and thanksgiving in the way in which I use them is that we really need different terms for our experience. There are moments in which gratitude wells up in our hearts. We experience this first as if something were filling up within us, but not yet articulate. And then comes the point where the heart overflows with gratitude, and we sing, and we thank somebody. I call that thanksgiving. And those two parts are really two phases of the process that is gratefulness." End quote.

So for Brother David, gratitude is the emotion, thanksgiving is the expression, and gratefulness is the whole thing.

He goes on to give us a visual: "Think of this as the bowl of a fountain. As it fills up, it's very quiet and still. And then when it overflows, it starts to make noise, and it sparkles and it ripples. And that is really when the joy comes to itself, so to say, when gratitude becomes articulate as thanksgiving.

And for us, for many people in our culture, the heart fills up with joy, with gratefulness, and just at the moment when it wants to overflow, right at that moment--the advertisement comes in and says no, there's a better model, and there's a newer model, your neighbor has a bigger one.

And instead of overflowing, the bowl gets bigger and bigger. And it never overflows. That means it always flows in, it doesn't overflow, it flows in and in and in and chokes us eventually.

And in other places, we see very poor people who, compared to us, have practically nothing. But they are so joyful. All the time grateful and joyful, because one little drop is enough for the bowl to overflow. Their bowl is small. So we can learn from that.

We don't have to deprive ourselves of everything, but we can learn from that."

Sample Questions

What do you think of the fountain metaphor? And how might it apply your life?

No example answer.

What is something that you are really grateful for?

No example answer.

What could it look like for that gratitude to overflow as thanksgiving?

No example answer.

How much is enough? (Left intentionally vague.)

No example answer.

What if you already have more than enough? (Left intentionally vague.)

No example answer.

Gathering Agenda

🚧 under construction 🚧

This section is still being written. We are working on...

1) A 2-5 minute primer meant to bring new folks up to speed and refresh memories.

2) A handful of carefully selected questions to get your community talking.

Click below to see a completed Gathering Agenda.

Sample Questions

What do you think of the fountain metaphor? And how might it apply your life?

No example answer.

What is something that you are really grateful for?

No example answer.

What could it look like for that gratitude to overflow as thanksgiving?

No example answer.

How much is enough? (Left intentionally vague.)

No example answer.

What if you already have more than enough? (Left intentionally vague.)

No example answer.