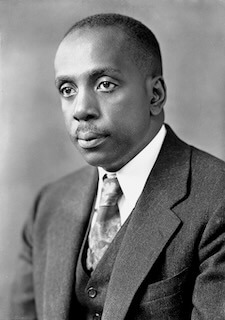

Scurlock Studio Records © All rights reserved.

To be Loved is to be Understood

To be Loved is to be Understood

Video

Audio

Transcript

Now one other picture. And then we will struggle a little with the idea of the subject. I will get there. And this also comes from my own childhood.

When I finished the seventh grade in Daytona, I went to work, as all of our fellows did, because there was no eighth grade for us in our town of Daytona. And whenever my mother and grandmother and other home-owners petitioned the school board for high school for us, their stuck answer was, there is no child in town eligible for high school, because there is no child in town who'd finished the eighth grade.

So this kept. When I finished, my teacher felt that I had promise. And he asked my mother if she would ask the man for whom I was going to work to let me take two hours for lunch every day. And I would work an hour longer in the afternoon so that this teacher-- Professor Howard was his name-- could, on his lunch hour, teach me the eighth grade.

So he did. And at the end of the term in the spring, he said to the superintendent that I have a boy who is ready to take the eighth grade examination. And there was no such boy, in the mind of the superintendent, because there was no eighth grade. And then he told him what he'd done.

He said, well, I will not let you give him the examination, but I'll prepare it and give it. So he prepared it and gave it. And fortunately, I passed it. The next year, we got the eighth grade.

The problem was, to go on to high school, at that time-- I'll be through with this story in a minute. At that time, there were only three high schools for Negro children-- or as you say now, black children-- in the entire state of Florida. One was in Jacksonville.

And I had a cousin who lived in Jacksonville. And he said, if you can get to Jacksonville, you can live with us. And if you do all of the chores and things of that sort around the house, we will give you a room and a meal a day. Incidentally, the school was just four and a half miles away.

So the problem next was getting out of town. It was only 110 miles. But all the money that I made went to my mother and my grandmother and my two sisters to keep the house going-- my little part of it.

So when September came, I didn't have the $5.00. The railroad fare was $3.80. And I didn't have the $5.00.

Not only did I not have the $5.00, but I didn't have a trunk, because nobody in our house, our family, had ever been anywhere. So why would you have a trunk?

So a neighbor, whose son had gone to Tuskegee some 15 years before, gave me his old trunk. And it had no lock. It had no handles. So I put my things in it.

Then the problem was how to get the $5.00. But in those days, every child and every adult in our community had what was called a $0.10 policy-- a little sick-and-accident policy. If you had a dime a week when the man came around to collect, and when you got sick, you could get $5.00 if you filled out your blank. And then your problem was to be sure to stay in bed so when he came around, he wouldn't catch you up.

And then my mother sent for the family doctor, Dr. Stockins. And when he came, he gave me some medicine. And I said, I can't pay you for your visit until next summer, because I'm going to school with this money.

So I told everybody goodbye. And all the neighbors turned out. It was wonderful. And when I got to the railway station, I bought my ticket and wanted to check my trunk.

And the agent said, boy, you can't check your trunk on your ticket, because the regulation is that the tag has to be attached to the trunk, not to the rope. You'll have to send it by express. And I didn't have any money to do that.

So I sat down on the steps of the railway station, crying my heart out, because my dream was gone. I'd told everybody goodbye. I had my lunch that my mother had fixed for me.

Now the idea of going back home, not having left home, was a little more emotional than I could manage. And as I sat there crying with my hands over my eyes, when I opened my eyes, there were two big feet right down in front. And my eyes moved all the way up until I looked into the face of this man.

He had on blue overalls, a blue bandanna handkerchief around his neck, and a sort of cap that trainmen wore. He took a sack of Bull Durham tobacco out of his pocket, opened it. Out of this pocket, he took his cigarette paper and, all with one hand, opened it, put the cigarette in the paper-- the tobacco in the paper-- rolled it, sealed it with saliva, put it in his mouth, tightened the cord, put it back in his pocket.

Out of another pocket, took a kitchen match, and on his thumb, he struck it. He lighted the cigarette, inhaled deeply, and as the smoke came out, he said, boy, what the hell are you crying about? And I told him. And I hear, he said, if you're trying to get out of this town to make something out of yourself, the least I can do is to help you.

So he took me around to the agent. And he said, how much does it take to send this boy's trunk to Jacksonville? The agent told me. He counted the money out from a leather pouch.

The agent wrote the receipt, gave the receipt to him. He gave the receipt to me. And he turned and walked out to the track and disappeared down the track. He had never seen me before. I had never seen him before.

I did not know who he was. He did not know who I was. But because of this special moment of grace, I'm here tonight.

Now this announced to me that, in and of myself, I was of worth, of worth, of worth. And since that time, I have not worn blinkers. And I know how hard life is. But there never has been a moment when the glow of that benediction has not illumined the darkest corner in which I've lived.

Now that's the prologue. Now you've had a chance to rest a little. So let's go to work.

[LAUGHING]

The search for meaning in man's experience of love. To love means-- and this is the proposition. To love means to deal with another human being at a point in that human being that is beyond all of his faults and all of his virtues. Now let me say it again, because there's no hurry.

To love is to deal with another human being at a point in that human being that is beyond all of his faults and all of his virtues. And to be loved is to have a sense of being touched at a point in you that is beyond all your faults and all your virtues.

This means, then, that I must feel. However I start out, I must feel that, in this experience, that at last I am being understood. If I were to ask you tonight, just if you had one wish, stripped of all other wishes, my guess is, after you dismissed all such things as money in the bank and a car and health and all the tiddly winks, it would be a feeling that I am understood-- that for one swirling moment, it is unnecessary for me to pretend anything-- just to be me, undisguised, naked, exposed, completely vulnerable, and utterly secure.

Gathering Agenda

Below is a sample summary and question that could be used for an in-person gathering. Or you can use it inspiration as you craft your own. You know your community best.

Summary

Howard Thurman is a story teller. He has a gift for taking abstract theological ideas and putting them on display as short stories. This week's sermon includes one such story of a random stranger on a random train platform whose kindness gave Thurman a future. Instead of retelling that story here, I'm going to share another Thurman story. This one comes to us secondhand by way of a conversation between Krista Tippett and Rev. Otis Moss III. Reference.

Rev. Moss begins "...here's a Thurman story that I absolutely love — the story goes that Thurman's grandmother owned some land. And there was a white woman who was adjacent to the land and did not like the fact that this Black woman owned land. And so she decided she was gonna get back at Thurman’s grandmother. She went to her chicken coop and got all the manure and dumped it on Mrs. Thurman's land. On her tomatoes and her greens and everything she was growing, to destroy it.

Mrs. Thurman, when she realized this manure had just destroyed everything, she decided take the manure and mix it in with the soil. And so the woman would dump at night, and each morning Thurman’s grandmother would get up and turn it over and mix it.

After some time the woman next door eventually fell ill — and she wasn’t just mean to Black people, she was mean to everybody, so nobody came to see her. Seeing her adversary was weak, Thurman’s grandmother went next door, not with a heart full of revenge but with two hands full of flowers. She knocked on the door and heard a frail voice. The woman was completely shocked that this Black woman, whom she had been so cruel to, would come and see her. And she was so deeply moved by the kindness.

Thurman’s grandmother placed the flowers next to the woman, and the woman said, 'These are the most beautiful flowers I’ve ever seen. Where’d you get them?' Thurman’s grandmother said, 'You helped me make them, because when you were dumping in my yard … I decided to plant some roses.'

Howard Thurman talks about from the manure, what can blossom. There are some who allow the manure to fall on them, and others who just turn over the soil to make something new."

In these stories, we find two testaments to the power of kindness. It reminds us that to love is to recognize and engage with someone beyond their imperfections and strengths. This kind of love, understanding, and acceptance, is what we all, at our core, yearn for: to be truly understood and embraced for who we are, without pretense or disguise.

As we gather here, let's reflect on these stories and the broader implications they hold for our lives. These stories are a call to action, a reminder of the transformative power of love, and the impact a single act of kindness can have on a person's life. Each of us has the potential to be that kind stranger on the platform or a neighbor who can work with the hatred until it blossoms into love.

Sample Questions

Do Thurman's stories remind you of someone in your life?

Thurman guessed that if you had one wish - you would wish to be understood. Did he guess right?

Who understands you better than anyone else? How do they do it?

Gathering Agenda

🚧 under construction 🚧

This section is still being written. We are working on...

1) A 2-5 minute primer meant to bring new folks up to speed and refresh memories.

2) A handful of carefully selected questions to get your community talking.

Click below to see a completed Gathering Agenda.